Using heuristics and biases for marketing

Everyday we are bombarded with a surplus of information and questions. To cope our brains have developed cognitive short cuts known as heuristics. They can be thought of as efficient, simple rules, learned, or instilled by evolutionary processes. These allow us to make decisions and judgments quickly without having to analyse all the factors involved, especially if important information isn’t present. Our lives would become unbearable if we were forced to construct a pros and cons list for every decision we make. For example, rather than deciding what to wear each day, you may have some ‘default’ outfits. Or when looking at a dinner menu with lots of options, you may choose what you have enjoyed in the past. Due to this, heuristics are not about making the perfect decision but making one quickly.

The concept of heuristics was first introduced by Nobel-prize winning psychologist Herbert Simon in the 1950s. He proposed that while we strive to make rational choices, all humans are fundamentally flawed in that our brains are subject to cognitive limitations. In other words, our mind needs ways to reduce effort, increase speed, and often maintain our blissful ignorance of reality. His work laid a foundation that was expanded upon by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s. It was Kahneman that developed the idea of thinking fast and slow known as system 1 and system 2 thinking, which is vitally important in heuristics. The system 1 brain is characterised as being unconscious, automatic, and effortless (sometimes referred to as the ‘caveman’ brain). Its role is to assess the situation and deliver fast updates. System 2 however is characterised as logical, conscious, and deliberate allowing us to seek out new and missing information to arrive at complex conclusions.

“Thinking is to humans as swimming is to cats; they can do it, but they’d prefer not to.” Daniel Kahneman

Heuristics mainly fall into the category of system 1 thinking which accounts for about 98% of our choices. These studies have lead to the establishment over 25 heuristics or biases, that through behavioural research and experiments, explain why we make very similar judgements and decisions.

How biases can improve advertising effectiveness

One of these heuristics is known as the bystander effect. It is the reduced lack of responsibility we feel watching a crime unfold in a crowd of people as opposed to being the only person who witnessed it. A great example of this was detailed in the brilliant book ‘The Choice Factory’ by Richard Shotton. He looked at how the UK NHS revised its ‘Give Blood’ campaign in light of low blood stocks around the country. Originally the ads said, “Blood stocks are low across the UK”. The ads were subsequently changed to “Blood stocks are low in Birmingham (or Leeds or Manchester), please help”. By including a regional message the target audience becomes more involved as the issue is brought closer to home. In just two weeks they saw a 10% improvement in the cost per donation.

Another example of this subconscious thinking is related to the placebo effect. A remarkable phenomenon in which a placebo, a fake treatment containing an inactive substance or characteristic, can improve a patient’s condition simply because they have the expectation that it will be helpful. Anton De Craen, a clinical epidemiologist at the University of Amsterdam, systematically reviewed 12 studies looking at the effect of colour on painkiller effectiveness.

Another example of this subconscious thinking is related to the placebo effect. A remarkable phenomenon in which a placebo, a fake treatment containing an inactive substance or characteristic, can improve a patient’s condition simply because they have the expectation that it will be helpful. Anton De Craen, a clinical epidemiologist at the University of Amsterdam, systematically reviewed 12 studies looking at the effect of colour on painkiller effectiveness.

He concluded that red painkillers were consistently more effective than blue painkillers, a fact that is surprisingly underused when designing their appearance. This is because our brains associate the colour red with power and strength, while we associate blue with the calmness of the sky and ocean. Obviously, we value strength when it comes painkillers.

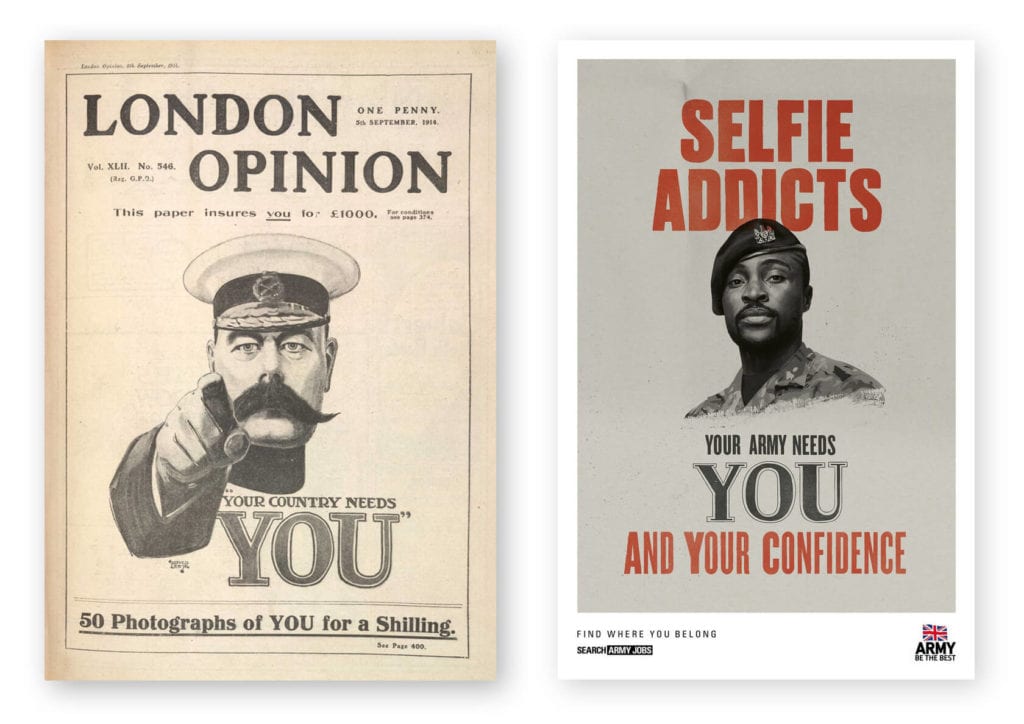

Lord Kitchener Wants You is a 1914 advertisement by Alfred Leete which was developed into a recruitment poster. It depicted Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, above the words “YOUR COUNTRY NEEDS YOU”. In 2019 the British Army reused this concept in their recruitment campaign to great effect. Both posters utilise a bias called The Cocktail Party Effect, where the viewer is more engaged by the personal relevance of the content. In the same way that you can often hear your own name mentioned in conversation across a noisy room at a party – our brains filter the sound that’s most relevant to us.

The science of marketing

This is all good news for marketing as heuristics lead to cognitive biases, meaning they can be applied to gain a competitive advantage. We are living in a time in which the way we are exposed to information and media is rapidly changing and we have to be able to adapt. Therefore, marketing managers need to understand the psychological processes behind consumer action. The importance of this was highlighted by Richard Shotton when he said “you wouldn’t trust a doctor with no knowledge of physiology or an engineer ignorant of physics … it’s foolhardy to work with an advertiser who knows nothing of behavioural science”.

Many of these marketing strategies contrast with traditional anecdotal marketing. For years we have been guided by assumptions of what we think consumers do, often to go so far as to directly ask them. However, what we say and what we do are often very different things due to subconscious decision making. David Ogilvy, founder of Ogilvy and Mather advertising agency, famously said;

“The problem with market research is that people don’t think how they feel, they don’t say what they think and they don’t do what they say”.

So when designing your next marketing campaign based solely on extensive consumer market research, remember David’s words and reach for the salt. Consequently, heuristics offer marketers an often untapped resource to guide creative thinking and marketing strategies to deliver greater effectiveness.

Below are a few books if you want to explore this fascinating subject further:

– The Choice Factory by Richard Shotton

– The Wiki Man by Rory Sutherland

– Inside the Nudge Unit by David Halpern

If you’d like to talk to us about your marketing challenges, contact us at [email protected] or call 01279 797 250 and ask for Lawrence or Anthony.